May 02, 2019 We recommend — Shakespeare’s Representation of Weather, Climate and Environment: The Early Modern ‘Fated Sky’

“…the medieval period had been dominated by a theological vision in which weather and climate reflected God’s direct action upon nature. In the first half of the sixteenth century, Luther still thought that the various manifestations of the weather testified to God’s presence.”

Shakespeare’s Representation of Weather, Climate and Environment: The Early ‘Fated Sky’

Sophie Chiari

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019

PR3039 C45 2019

General Collection, Level 2

From the publisher: “While ecocritical approaches to literary texts receive more and more attention, climate-related issues remain fairly neglected, particularly in the field of Shakespeare studies. This monograph explores the importance of weather and changing skies in early modern England while acknowledging the fact that traditional representations and religious beliefs still fashioned people’s relations to meteorological phenomena. At the same time, a growing number of literati stood against determinism and defended free will, thereby insisting on the ability to act upon celestial forces. Sophie Chiari argues that Shakespeare reconciles the scholarly approaches of his time with popular views rooted in superstition and promotes a sensitive, pragmatic understanding of climatic events. Taking into account the influence of classical thought, each of the book’s seven chapters addresses a different play where sky-related topics are crucial and considers the way climatic phenomena were presented on stage and how they came to shape the production and reception of Shakespeare’s drama.”

Sophie Chiari is Professor of Early Modern English Literature at Clermont Auvergne University, France.

Rare Books at the J. Willard Marriott Library goes to Edinburgh via France and joins these venerable institutions in contributing to Professor Chiari’s work: Huntington Library, Bodleian Library, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Magdalen College, British Library, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Cornell University Library.

“The comparison with hell, in particular, was so fruitful that it was captured in a number of maps charting the New World and displaying personified winds associated with devilish creatures. For instance, from 1544 onwards, a world map drawn in 1540 by the Dutch cartographer Gemma Frisius was inserted in Petrus Apianus’s Cosmographia. On this heart-shaped map, the winds appear in the shape of bearded old men in the top left-hand corner and as curly-haired children blowing out little suns in the right-hand corner, while, in the bottom parts, they are frightening skulls with dishevelled hair and sharp teeth. These hot, plague-bearing winds are actually presented as fire-breathing devils.” — Sophie Chiari, Shakespeare’s Representation of Weather, Climate and Enviroment

Charta Cosmographica

Peter Apian (1495-1552)

Antwerp: s.n., 1540-64

GT3200 1540 A65

“My thanks more particularly go to Anne Chesher, Deputy Librarian at Magdalen College, who helped me locate an engraving in John Harding’s copy of the Bible, and to Luise Poulton, Managing Curator at J. Willard Marriott Library, who drew my attention to the 1551 Paris edition of Peter Apian’s Cosmographia. — Sophie Chiari, Shakespeare’s Representation of Weather, Climate and Environment

Cosmographia

Peter Apian (1495-1552)

Paris: D. Martini, 1551

GA6 A48

Peter Apian, pioneer in the development of astronomical and geographical instruments, was born in Germany and taught at the university in Ingolstadt. A cartographer, astronomer, and mathematician, Apian first published the famous Cosmographia, his greatest work, in 1524. In this book Apian first suggested that lunar distances could be used to measure longitude. (Precise calculations for longitude would not be perfected until the eighteen century). Among the numerous illustrations showing various globes, spheres, maps, diagrams, astronomical constellations and instruments with their applications, the most famous is a reproduction of the now-lost 1540 heart-shaped world map by Gemma Frisius (1508-1555).

Chiari uses many first and early editions of works for her scholarship. We have several of her sources for your use:

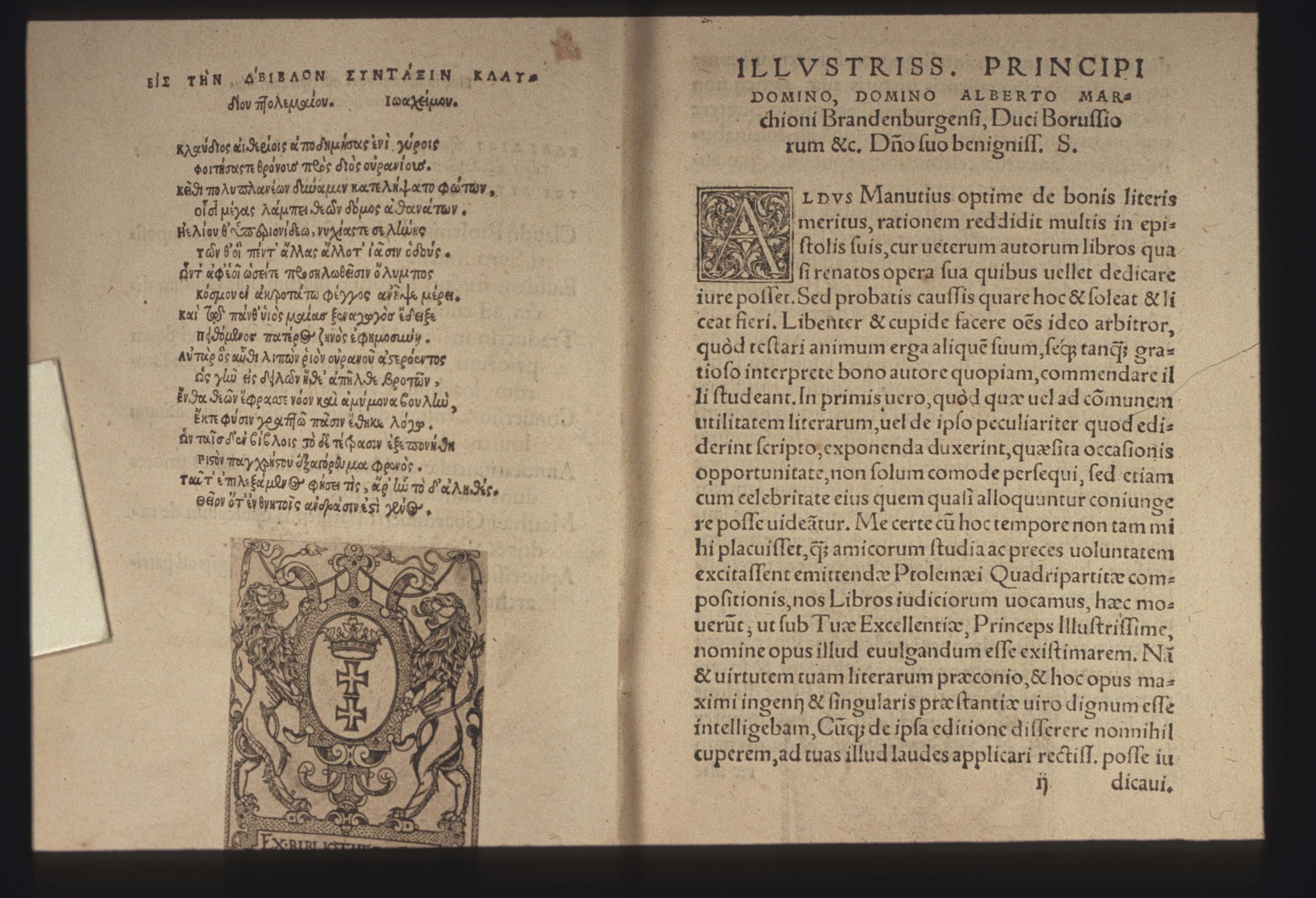

“One should not either understimate the serious impact of the Ptolemaic tradition as, in the second century AD Claudius Ptolemy also established methods for meteorological forecasts in his Four Books (Tretrabiblos), a treatise in which he explains that the heavenly bodies affect events on earth. In the sixteenth century, the work still had its adepts, as Shakespeare ironically shows in King Lear, and it circulated in various manuscripts before a Latin translation was issued in Nuremberg in 1535.” — Sophie Chiari, Shakespeare’s Representation of Weather…

Hoc in libro nunqua[m] ante typis aeneis in lucem…

Ptolemy (2nd century)

Nuremberg, Ionnem Petreium, 1535

PA4404 Q3 1535

Editio princips in Greek. This work was first printed in Venice in 1484 in a different translation. The Greek text of Ptolemy’s “Tetrabiblos” (so called because it consists of four books) and that of the “Karpos” (a collection of 100 ‘karpos’ in Greek – astrological aphorisms erroneously attributed to Ptolemy) are followed by the first edition of Joachim Camerarius’ Latin translation of the first two books and of passages from the third and fourth of the Tetrabiblos (there is some disagreement among scholars as to whether these last two are Camerarius’ translations), and by Giovanni Pontano’s Latin version of the Karpos. Next come seven pages of annotations by Camerarius on the first two books of the Tetrabiblos, Matthaeus Guarimbertus’ complete translation of the third and fourth books of the Tetrabiblos. Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos is considered one of the most important astrological textbooks of antiquity. The Greek text here is well-printed and interspersed with graphic symbols representing the zodiac and the most important planets and stars. A chart explaining these ‘abbreviations’ is at the beginning of the book.

“In The Secret Miracles of Nature, originally published in 1561, the Dutch physician Levinus Lemnius writes that ‘women are subject to all passions and perturbations […]a woman enrages, is besides her selfe, and hath not power over her self, so that she cannot rule her passions, or bridle her disturbed affections, or stand against them with force of reason and judgement.’ Even though it was only translated into English during the second half of the seventeenth century, Lemnius’s Latin work began to circulate in the 1560s and its views became highly influential among scholars and men of science…” — Sophie Chiari, Shakespeares Representation of Weather…

De miracvlis occvltis natvrae

Levinus Lemnius (1505-1568)

Antverpiae : ex officina Chrisophori Plantini, Architypographi Regij, 1581

BF1410 L4

Levinus Lemnius was a physician and astrologer who studied medicine at the University of Louvain under Robert Dodoens, Conrad Gesner and the great anatomist Andreas Vesalius. He returned to his native city of Zierikzee, where he set up practice and continued studying hygiene, geography, botany and astrology. Lemnius was particularly interested in unexplained phenomena. This book is a collection of wonders and oddities, the occult and folk beliefs. The Secret Miracles of Nature was first printed in Antwerp in 1559. It was extremely popular in its day, going through several editions during the rest of the sixteenth century and seventeenth century.

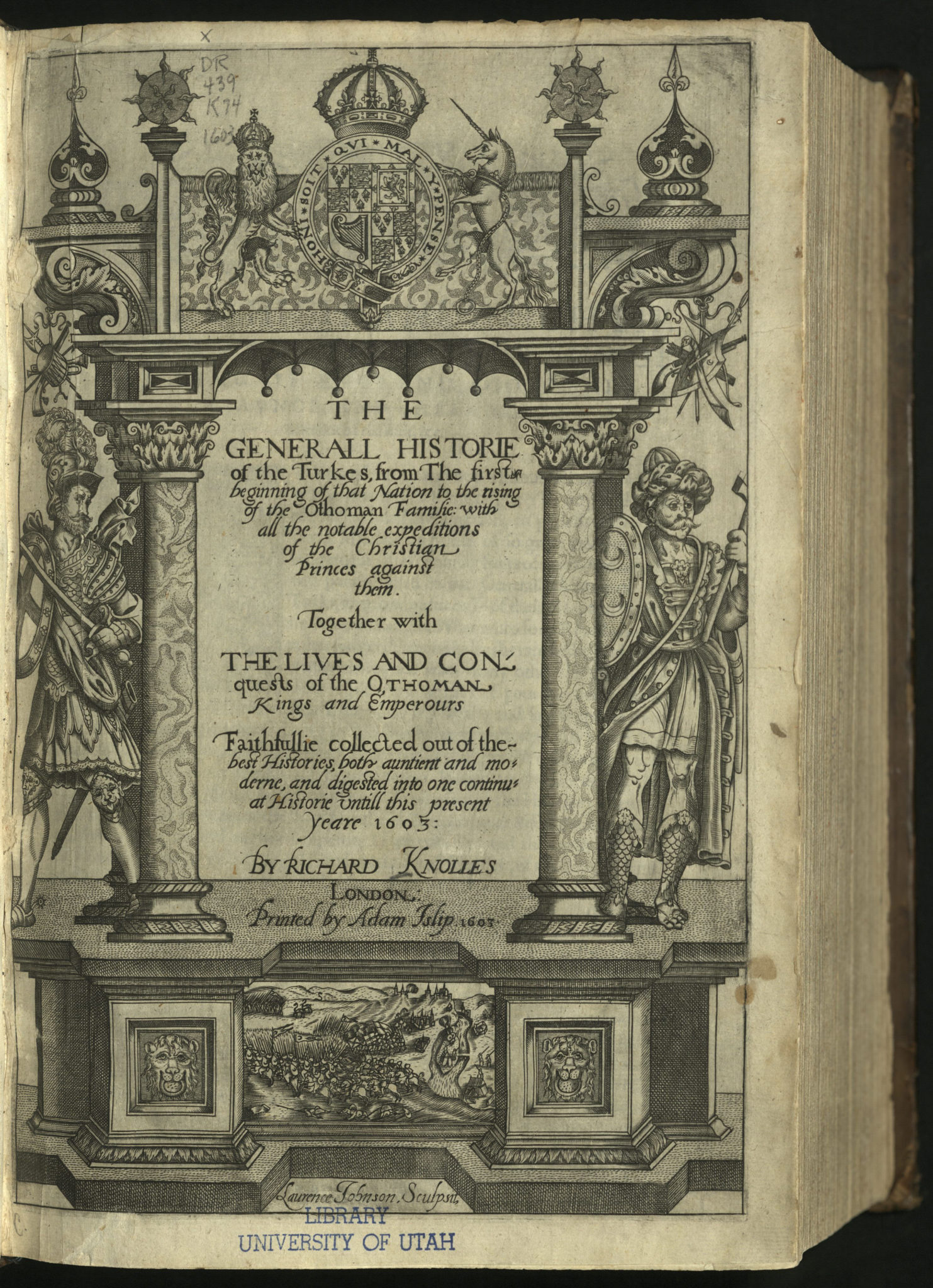

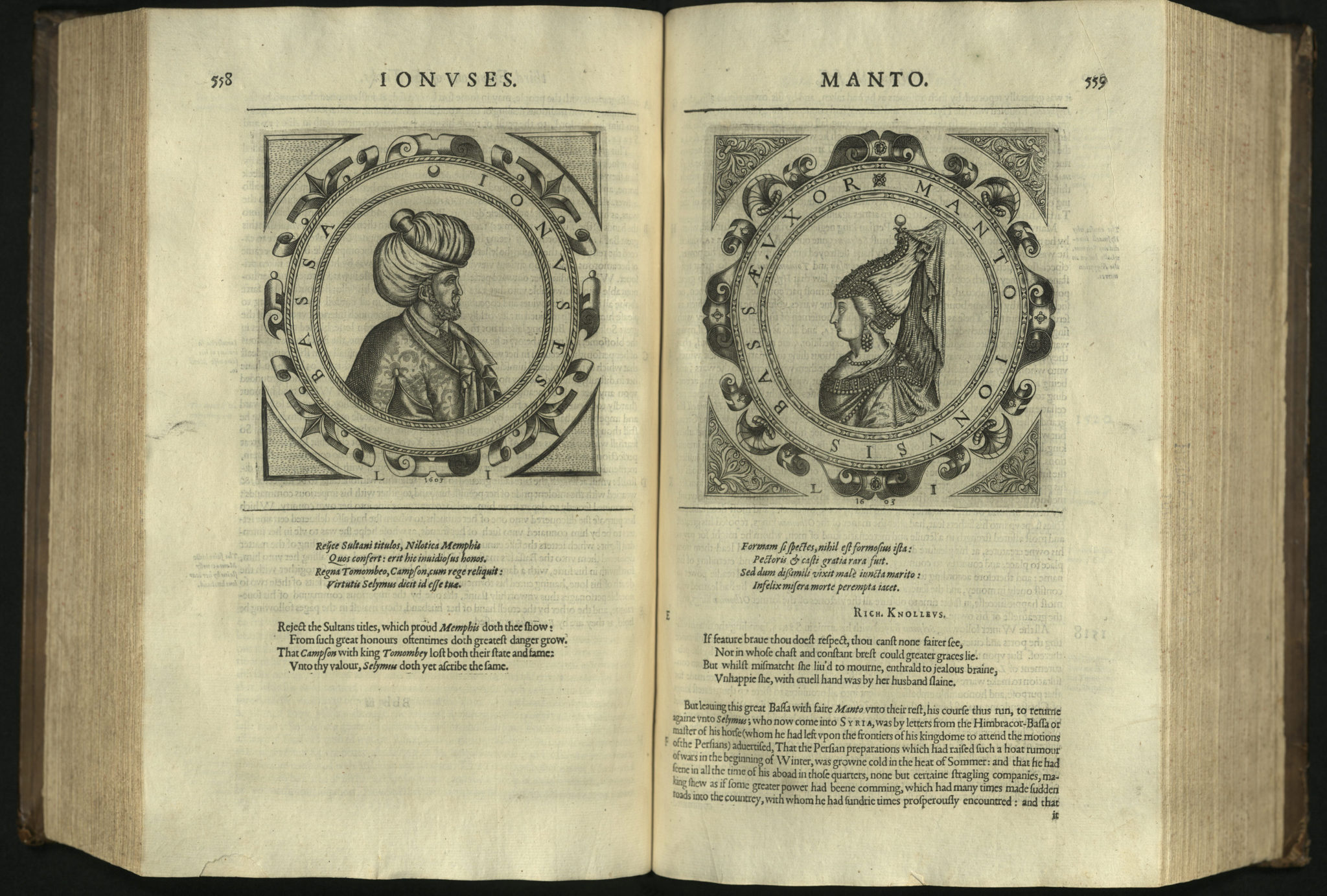

“In his Generall historie of the Turkes (1603), Richard Knolles does not only celebrate the ‘great and notable battell between the Turks and the Christians, commonly called, the battle of Lepanto’, he also reminds his readers of the major “losse of Cyprus”, acknowledging that the conquest of the island had been a crucial victory for the Ottomans…The renewed evocation of such an infamous episode in Knolles’s Generall historie did nothing, of course, to alleviate the fear of the Ottoman savagery. The alert Jacobean playgoers who attended a performance of Othello would certainly notice that the first scene of act 2, taking place in a fortified place presumably protected from the elements, was reminiscent of Famagusta…” — Sophie Chiari, Shakespeare’s Representation of Weather…

The Generall Historie of the Turkes, from The first beginning of that Nation to the rising of the Ottoman Familie: with all the notable expeditions of the Christian Princes against them

Richard Knolles

London, by Adam Islip, 1603

First Edition

DR439 K74 1603

“The people therein generally liued so at ease and pleasure, that therof the island was dedicated to Venus, who was there especially worshipped, and therof called CYPRIA.” — Richard Knolles, The Generall historie of the Turkes as quoted by Sophie Chiari, Shakespeare’s Representation of Weather…

“Florio regarded clima or ‘climate’ as ‘the dividing of heaven and earth, a clime’, a definition echoed in Randle Cotgrave’s Dictionarie of French and English Tongues where climate is defined as ‘a division in the skie, or portion of the world, beweene South and North’. — Sophie Chiari, Shakespeare’s Representation of Weather…

“Florio regarded clima or ‘climate’ as ‘the dividing of heaven and earth, a clime’, a definition echoed in Randle Cotgrave’s Dictionarie of French and English Tongues where climate is defined as ‘a division in the skie, or portion of the world, beweene South and North’. — Sophie Chiari, Shakespeare’s Representation of Weather…

A Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues

Randle Cotgrave (ca. 1569-1634?)

London: Printed by Adam Islip, 1611

First edition

PC2640 A2 C7 1611 oversize

The French word “crosse” is translated as “a crosier, or Bishops staffe; also a Cricket staffe; or, the crooked staffe wherewith boyes play at cricket,” the definition found in Randle Cotgraves’ dictionary. This is perhaps the earliest reference to cricket so spelt. The Oxford English Dictionary documents the first usage of the word “obesity” from the Latin, obesus, meaning “having eaten until fat” in this dictionary by Randle Cotgrave, the English lexicographer. With more than 48,000 headwords and nearly one million words, the dictionary was far larger than any of its predecessors. Cotgrave, like his father before him, attended the King’s School in Chester, which he left in about 1586 to attend St. John’s College, Cambridge. While there, Cotgrave met William Cecil, Lord Burghley, son of the Earl of Exeter, and worked as Cecil’s secretary. Dictionarie is dedicated to Cecil. Cecil spoke French and Cotgrave credit’s Cecil with both the time Cecil granted him to work on the dictionary and Cecil’s knowledge of that language. Jean Beaulieu, who worked for the British Ambassador to France, was a friend of Cotgrave and checked much of the text of the dictionary before publication. While Cotgrave used earlier and then well-known dictionaries, he read also read books, old and new, in all dialects, finding words not used for hundreds of years. He included these in his dictionary, to be noted, used or not, as the reader chose. The dictionary provided meanings, the gender of nouns, the formation of the feminine adjectives, and a collection of illustrative phrases, idioms and proverbs — all expected components of our dictionaries today. It included proper names and the parts of France from which words were thought to derive. Cotgrave included at the end a guide for teaching oneself French, giving pronunciations and grammar. Cotgrave presented a copy of the dictionary to Prince Henry, for which he was given a gift of 10 [pounds]. The dictionary sold well, going through five revised editions through 1672. Woodcut title border.

“Whenever his characters happen to blame climate for their misfortunes, he suggests on the contrary that such an attitude can only work as an excuse at worst, as a symptom at best: the real causes of disgrace and failure are to be men and women’s responsibility rather than to the ‘ways of God to men’ (Milton, Paradise Lost, I, 26).” — Sophie Chiari, Shakespeare’s Representation of Weather…

PARADISE LOST. A POEM IN TWELVE BOOKS…

John Milton (1608-1674)

Printed by Miles Flesher, for Richard Bentley, at the Post-Office in Russell-street, 1688

First illustrated edition

PR3560 1688

“Far from Decartes’s mind/body dualism, [John] Locke called ‘sensory experience […]the only genuine source of knowledge…Unsurprisingly, in this Thoughts Concerning Education (1693), he advised parents to let their children experience the adversity of climate and to reconcile them with the cold and the rain characteristic of his country: ‘Plenty of open air […] not too warm and strait clothing; especially the head and feet kept cold, and the feet often used to cold water and exposed to wet.’ Because, ‘the strength of the body is chiefly in being able to endure hardships. so also does that of the mind’, Locke added.” — Sophie Chiari, Shakespeare’s Representation of Weather…

Some Thoughts Concerning Education

John Locke (1632-1704)

London: Printed for A. and J. Churchill, at the Black Swan in Pater-Noster-Row, 1693

First edition

LB475 L6 A3 1693

Published anonymously, the first edition of Some thoughts appeared before John Locke had made corrections. He was so incensed at its publication that he demanded it be suppressed. Some thoughts introduced the beginning of modern developmental psychology. In this sense Locke anticipated Jean-Jacques Rousseau in his advocacy of the “natural child,” who was to be toughened by exposure to the elements and fed only when hungry. Locke also addressed the moral education of children, stressing the importance of restraint and reason in molding a child’s mind. Two nearly identical editions of Some Thoughts were published in 1693. The two editions are most easily distinguished by the position of the rules and ornaments on the title pages and a change in line 19, A3 verso. In this edition line 19 has “Patronnge;” the other, corrected edition has “Patronage.” There is still disagreement among bibliographers over which is the first issue.

Come hold your books!

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.